Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome Cancer Risk Calculator

Your Risk Assessment

Quick Takeaways

- Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome (ZES) causes high levels of gastrin, leading to excess stomach acid.

- Chronic acid damage and gastric mucosal changes raise the chance of gastric cancer.

- Symptoms often include severe ulcers, diarrhea and abdominal pain.

- High‑dose proton pump inhibitors, surgery and somatostatin analogues are the main treatments.

- Regular endoscopic surveillance is recommended, especially for patients with MEN1.

What Is Zollinger‑Ellison Syndrome?

When you first hear the name Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome is a rare neuroendocrine disorder in which one or more gastrin‑producing tumors (gastrinomas) develop, typically in the pancreas or duodenum. These tumors secrete far more gastrin than normal, driving the stomach to produce large quantities of hydrochloric acid.

The resulting hyperacidity erodes the lining of the stomach and duodenum, causing multiple, often treatment‑resistant peptic ulcers. While the condition itself is uncommon-affecting roughly 1 in a million people-its downstream effects can be serious, especially the increased risk of gastric cancer.

How Excess Gastrin Fuels Gastric Cancer

Gastrin does more than just tell the stomach to make acid. It also acts as a growth factor for the gastric epithelium. Over time, the constant bombardment of acid and the trophic influence of gastrin lead to several changes that set the stage for malignancy:

- Gastric cancer is a malignant tumor arising from the lining of the stomach, often linked to chronic inflammation and mucosal damage becomes more likely when the protective mucus barrier is worn away.

- Hyperplasia of enterochromaffin‑like cells, driven by high gastrin, creates a field of proliferating cells that can accumulate DNA errors.

- Acid‑induced inflammatory cytokines promote a micro‑environment that supports neoplastic transformation.

Studies published in the early 2020s show that patients with ZES have a 2‑3‑fold higher incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma compared with the general population, especially when the syndrome is part of Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type1 (MEN1).

Who Is Most Likely to Develop ZES‑Related Cancer?

Two patterns emerge:

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia type1 is an inherited disorder that predisposes carriers to tumors of the parathyroid, pituitary and pancreas, including gastrinomas. MEN1 patients often develop multiple small gastrinomas, leading to long‑standing hypergastrinemia.

- Sporadic ZES, where a single gastrinoma arises without a genetic backdrop, still carries risk, but the cancer rate is slightly lower than in MEN1.

Age, smoking, and a history of Helicobacter pylori a bacterium that infects the stomach lining and causes chronic gastritis infection further amplify the danger. If a patient already has atrophic gastritis from H.pylori, the additive effect of gastrin‑driven hyperplasia can speed up malignant change.

Spotting the Signs: Symptoms and Diagnosis

Most patients notice the classic ulcer symptoms first-burning epigastric pain, especially after meals, and ulcers that refuse to heal despite standard therapy. Diarrhea, often greasy and foul‑smelling, shows up when excess acid inactivates pancreatic enzymes.

Diagnosis hinges on a few key tests:

- Fasting serum Gastrin is a hormone that stimulates gastric acid secretion; levels above 1,000 pg/mL strongly suggest ZES.

- Secretin stimulation test: secretin paradoxically raises gastrin in ZES patients.

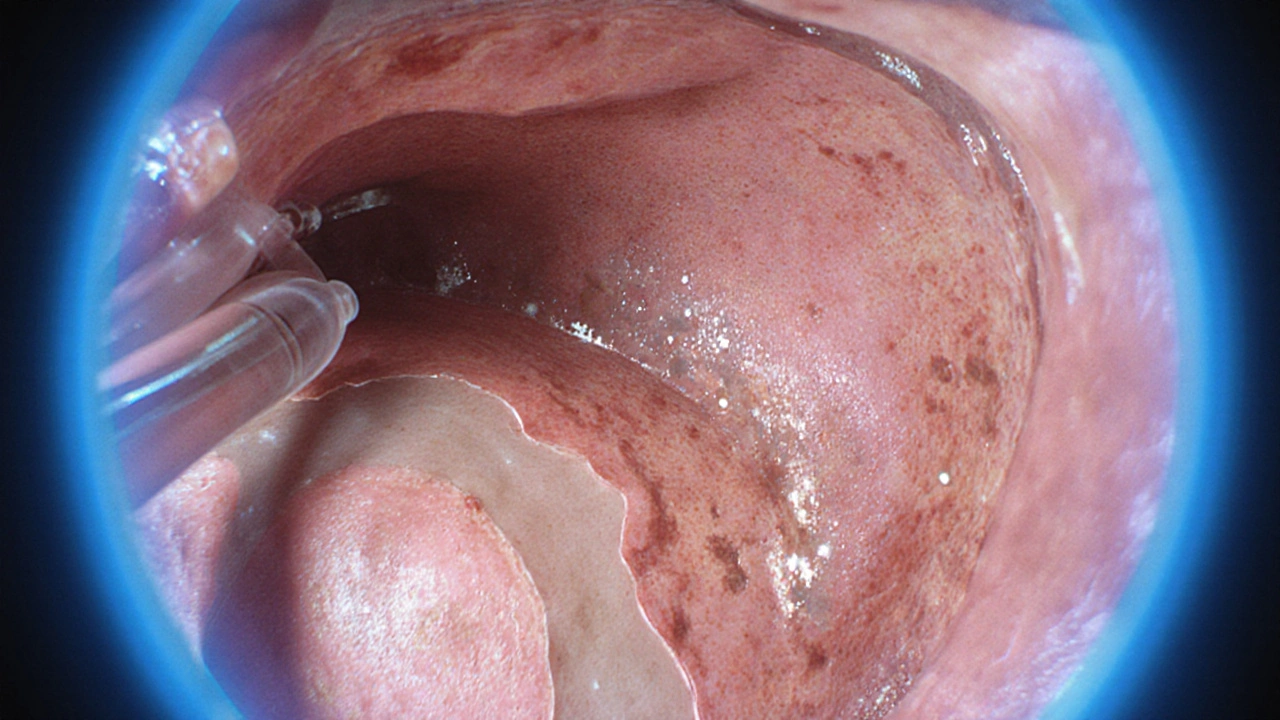

- Endoscopic ultrasound provides high‑resolution images of the pancreas and duodenum, helping locate tiny gastrinomas with a detection rate over 80% for lesions >5mm.

- CT or MRI for staging if metastatic disease is suspected.

Biopsy of suspicious gastric lesions is essential. Pathology labs frequently report the Ki‑67 proliferation index a marker that quantifies how many tumor cells are actively dividing, guiding prognosis. A Ki‑67 score above 5% in a gastrinoma raises concern for aggressive behavior.

Taming the Acid: Treatment Options

The first line of defense is medical control of acid output. Proton pump inhibitors are drugs that block the final step of acid secretion in stomach parietal cells are used at doses 10‑100mg three times daily-far higher than typical GERD regimens. This approach heals ulcers in >90% of cases and buys time for definitive tumor management.

When tumors are localized and resectable, surgery offers the best chance for cure. Enucleation of the gastrinoma or pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple) may be performed, depending on size and location.

For unresectable or metastatic disease, Somatostatin analogues such as octreotide or lanreotide bind to somatostatin receptors, reducing gastrin release and tumor growth are the mainstay. Newer targeted agents (e.g., everolimus) and peptide‑receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) have shown promise in small trials, but cost and availability remain hurdles.

Regardless of the approach, lifelong acid suppression is usually required because even small residual gastrinomas can reignite hyperacidity.

Screening for Gastric Cancer: Guidelines & Table

Because the cancer risk is real, most experts recommend a structured endoscopic surveillance plan. The exact schedule varies, but a common protocol looks like this:

| Patient Group | Relative Cancer Risk | Suggested Interval | Key Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEN1‑associated ZES | ~3× general population | Every 1‑2years | High‑definition upper endoscopy with biopsies |

| Sporadic ZES (tumor <2cm) | ~2× general population | Every 2‑3years | Standard upper endoscopy |

| Post‑surgical remission | Baseline risk | Every 3‑5years | Endoscopy, targeted biopsies |

During each endoscopy, the endoscopist looks for atrophic changes, intestinal metaplasia, or any dysplastic lesions. If any abnormality is found, the surveillance interval shortens to six months.

Lifestyle Tweaks to Lower Your Odds

Medical therapy is essential, but patients can tilt the odds in their favor with a few everyday choices:

- Quit smoking - it doubles the risk of gastric cancer in hyperacidic environments.

- Limit alcohol intake; heavy use irritates the mucosa and interferes with healing.

- Follow a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables and fiber; antioxidants appear to counteract DNA damage.

- Eradicate any Helicobacter pylori infection with a clarithromycin‑based triple therapy; this removes a separate carcinogenic stimulus.

- Maintain regular follow‑up appointments; skipping a surveillance endoscopy can delay detection of early cancer.

Key Takeaway

Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome dramatically raises the chance of developing gastric cancer because of relentless acid production and gastrin‑driven cell growth. Early diagnosis, high‑dose acid suppression, and a disciplined endoscopic surveillance schedule are the best defenses. Pair those medical steps with healthy habits, and you give yourself the strongest possible shield against cancer.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome be cured?

Surgery can remove the gastrinoma and potentially cure the disease, but many tumors are multiple or metastatic. In those cases, long‑term medical management with PPIs and somatostatin analogues controls symptoms but does not erase the underlying cause.

How often should I get an endoscopy?

If you have MEN1‑related ZES, aim for an upper endoscopy every 1‑2years. Sporadic cases usually need it every 2‑3years, and after successful surgery the interval can be extended to 3‑5years, provided no abnormal findings appear.

Is there a genetic test for ZES?

Yes. Testing for mutations in the MEN1 gene can identify inherited cases. Even without a MEN1 mutation, a sporadic gastrinoma may have somatic mutations that influence treatment decisions.

Do proton pump inhibitors increase cancer risk?

Current data do not show a direct link between high‑dose PPIs and gastric cancer. In ZES, the benefit of controlling acid far outweighs any theoretical risk, especially since acid itself is the main carcinogenic driver.

What symptoms should prompt an urgent doctor visit?

Sudden, severe abdominal pain, vomiting blood, black stools, or a new‑onset weight loss are red flags. These may signal ulcer perforation, bleeding, or an evolving cancer and need immediate evaluation.

Michelle Pellin

October 2, 2025Ah, the labyrinthine world of Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome unfurls before us, a cascade of gastrin‑driven chaos that threatens the very lining of the stomach. The article deftly paints the perilous link between hypergastrinemia and gastric carcinoma, reminding us that rare diseases can cast long, ominous shadows. With vivid prose, it maps the cascade from neuroendocrine tumors to relentless acid production, then to mucosal erosion and malignant transformation. The emphasis on MEN1‑associated risk is a clarion call for vigilant surveillance, and the risk calculator feels like a modern oracle for patients and clinicians alike. In short, this piece blends science with storytelling, delivering both knowledge and urgency.

Keiber Marquez

October 6, 2025this post is overcomplicated and dont need all that fancy stuff.

Lily Saeli

October 10, 2025One must contemplate the ethical weight of neglecting a condition that silently erodes our interior citadel. If gastrin, the humble messenger, is allowed to run rampant, we become complicit in the creation of our own demise. The moral imperative, therefore, is to heed the early warning signs, lest we surrender to an invisible tyranny of acid. The article serves as a reminder that medical complacency is a subtle vice, and that proactive surveillance is a virtue of the enlightened.

Joshua Brown

October 14, 2025First and foremost, the pathophysiology of Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome hinges on gastrin‑producing neuroendocrine tumors, which, through relentless hypersecretion, drive gastric acid output to supraphysiologic levels, thereby initiating a cascade of mucosal injury, ulcer formation, and ultimately, neoplastic transformation. The incremental risk of gastric adenocarcinoma, especially in the context of MEN1, is not merely a statistical footnote but a clinical reality that mandates a structured surveillance protocol, typically involving high‑definition upper endoscopy with targeted biopsies at intervals dictated by individual risk stratification. When evaluating a patient, it is essential to obtain a fasting serum gastrin level; values exceeding 1,000 pg/mL, particularly when corroborated by a positive secretin stimulation test, solidify the diagnosis and guide therapeutic decision‑making. Medical management should begin with high‑dose proton pump inhibitors, administered in divided doses to ensure continuous acid suppression, which not only promotes ulcer healing but also reduces the proliferative stimulus exerted by gastrin on the gastric epithelium. Surgical resection remains the definitive treatment for localized gastrinomas, and the choice between enucleation versus pancreaticoduodenectomy must be individualized based on tumor size, location, and the presence of metastatic disease. For patients with unresectable or metastatic lesions, somatostatin analogues such as octreotide or lanreotide provide dual benefits: attenuating gastrin release and exerting anti‑tumor effects; adjunctive therapies, including everolimus or peptide‑receptor radionuclide therapy, may be considered in refractory cases, bearing in mind their cost and availability constraints. Lifelong surveillance, however, is non‑negotiable; even after apparent disease control, residual microscopic gastrin‑secreting tissue can reignite acid hypersecretion, necessitating periodic endoscopic reassessment, typically every 1–2 years for MEN1 carriers and every 2–3 years for sporadic cases. It is also prudent to assess and eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection, as this bacterium synergizes with acid‑mediated damage to accelerate carcinogenesis. Patient education should emphasize smoking cessation, as tobacco compounds the carcinogenic milieu by promoting chronic inflammation and impairing mucosal healing. Finally, a multidisciplinary approach-encompassing gastroenterology, endocrinology, surgery, pathology, and nutrition-optimizes outcomes, ensuring that each facet of this complex disorder is addressed with expertise and compassion.

andrew bigdick

October 17, 2025Hey folks, I’m curious how many of you have actually tried the risk calculator in a real‑world setting, and what thresholds you ended up using for endoscopic follow‑up. It’d be great to hear diverse experiences, because the more perspectives we share, the better we can tailor surveillance to individual lives.

Shelby Wright

October 21, 2025Honestly, I find the whole “one‑size‑fits‑all” surveillance schedule a bit theatrical; why should a patient with a modest gastrin level be shackled to biennial endoscopies when lifestyle tweaks could tilt the odds? Let’s not forget that the narrative of inevitable cancer can become a self‑fulfilling prophecy, spurring anxiety that itself harms gastric health. In my view, a personalized, less alarmist approach might actually curb the very risk we’re trying to prevent.

Ellen Laird

October 25, 2025One must acknowledge the subtle elegance of integrating biochemical markers with endoscopic foresight, yet teh article, albeit comprehensive, occasionally lapses into pedestrian phrasing-perhaps a modest editorial revision would elevate its scholarly gravitas.

rafaat pronoy

October 28, 2025Cool stuff, thanks for breaking it down 😊. The calculator looks user‑friendly, and it’s good to see the emphasis on smoking and H. pylori as modifiable factors.

sachin shinde

November 1, 2025While the content is largely accurate, there are a few grammatical oversights that detract from its professional polish; for instance, “patients” should be possessive in “patients' risk,” and commas are needed before conjunctions in compound sentences. Such precision matters because clarity reinforces credibility, especially when discussing nuanced oncologic risk.

Leon Wood

November 5, 2025Stay hopeful, everyone! Even with a high‑risk label, proactive monitoring and lifestyle changes can dramatically shift outcomes. Remember, knowledge is power, and with the right team, you can turn the tide against gastric cancer.

George Embaid

November 9, 2025Friends, let’s celebrate the collaborative spirit of this discussion-each insight adds a piece to the puzzle of Zollinger‑Ellison management. Whether you’re a patient, a clinician, or just a curious reader, your perspective enriches our collective understanding.

Meg Mackenzie

November 12, 2025It’s hard not to wonder whether the pharmaceutical push for lifelong high‑dose PPI therapy is part of a larger scheme to keep patients dependent on costly meds, while the true solution-dietary overhaul and natural acid regulation-gets buried under a mountain of research grants aimed at drug sales. The same patterns repeat across many “rare” conditions, suggesting a coordinated agenda that benefits industry more than patients.