When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it’s truly the same? The answer lies in pharmacokinetic studies-the most widely used method to prove that a generic drug behaves the same way in the body as the original. Yet calling it the "gold standard" is misleading. It’s not perfect. It’s not always enough. And for some drugs, it’s barely even the best tool we have.

What Pharmacokinetic Studies Actually Measure

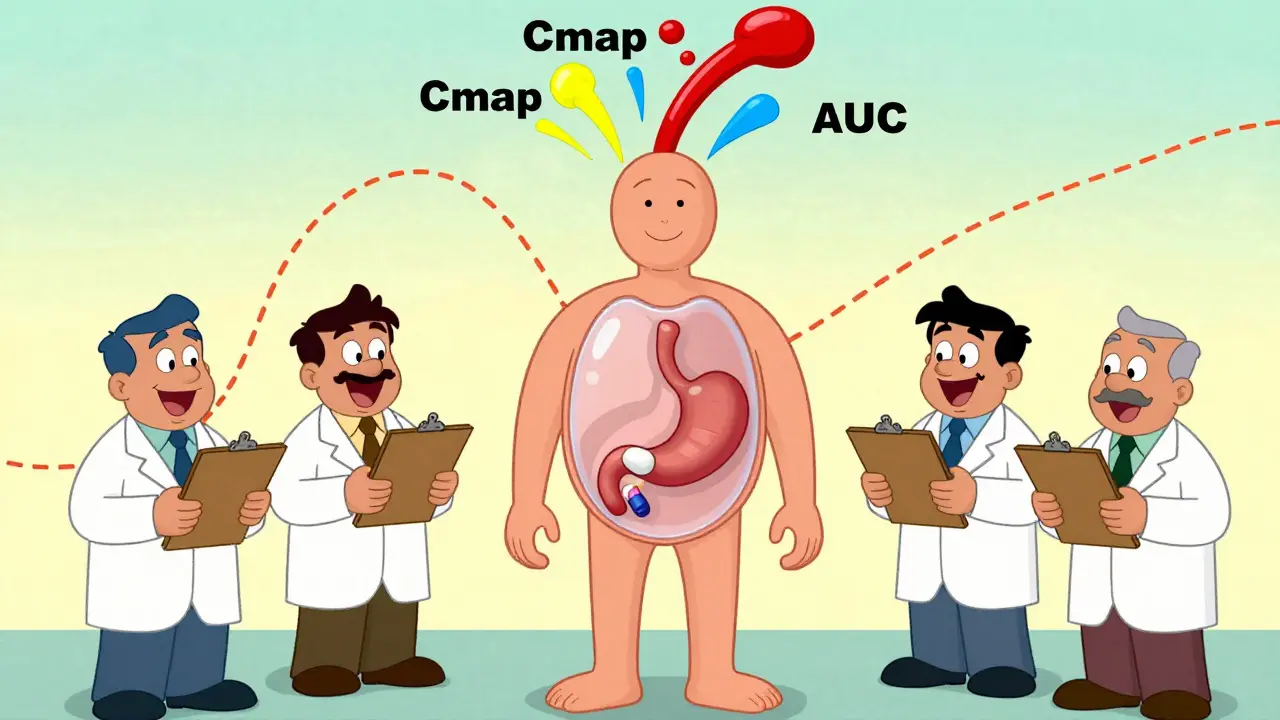

Pharmacokinetic studies track how a drug moves through the body. Specifically, they measure two key numbers: Cmax and AUC. Cmax is the highest concentration of the drug in your blood after you take it. AUC-area under the curve-shows how much of the drug your body absorbs over time. Together, they tell regulators whether the generic drug gets into your bloodstream at the same rate and in the same amount as the brand-name version.

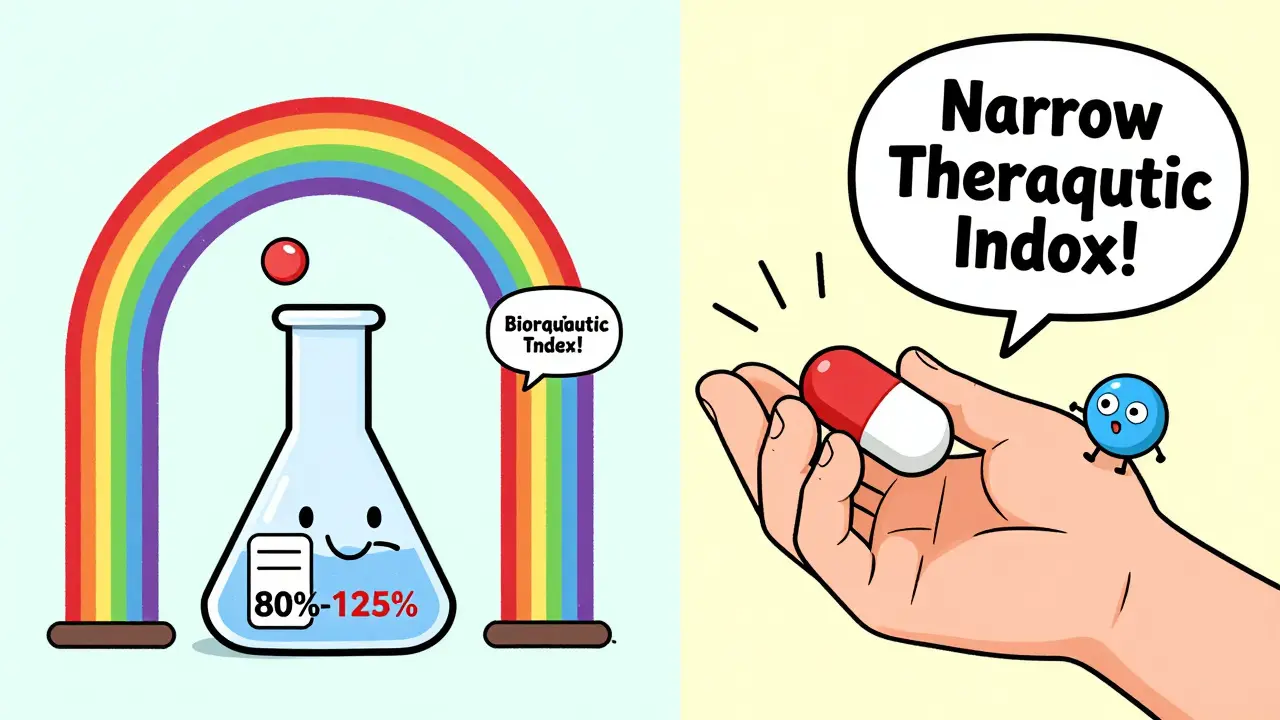

The FDA and other global agencies require that the 90% confidence interval for these values falls between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand drug gives you a Cmax of 100 ng/mL, the generic must deliver between 80 and 125 ng/mL. Sounds strict? It is. But here’s the catch: this range is based on statistical tolerance, not biological certainty. Two drugs can meet this rule and still behave differently in some patients.

These studies are done in healthy volunteers-usually 24 to 36 people-in a crossover design. Each person takes both the brand and generic versions, sometimes fasting, sometimes after eating. That’s because food can change how a drug is absorbed. For example, a generic version of a cholesterol drug might work fine on an empty stomach but fail when taken with a meal. That’s why both conditions are tested.

Why It’s Not Actually a "Gold Standard"

The FDA doesn’t call pharmacokinetic studies a "gold standard." They call them a "fundamental principle." Why? Because they’re a proxy-not a direct measure of what matters most: safety and effectiveness in real patients.

Take warfarin, a blood thinner with a narrow therapeutic index. A tiny difference in blood levels can mean a clot or a bleed. For drugs like this, the FDA tightens the bioequivalence range to 90-111%. Even then, there are documented cases where generics passed pharmacokinetic tests but caused unexpected side effects in patients. One 2010 PLOS ONE study found that two generics from reputable manufacturers had identical in vitro profiles and passed bioequivalence testing, yet their effects on blood clotting were significantly different. That’s not a failure of the test-it’s a failure of assuming that absorption equals outcome.

Pharmacokinetic studies measure what happens in the blood. But for drugs that act locally-like asthma inhalers, topical creams, or eye drops-what’s in the blood doesn’t tell you what’s happening at the site of action. A cream might absorb poorly into the bloodstream but still deliver the right dose to the skin. A standard PK study would call it "not bioequivalent," even if it works perfectly in practice.

When Pharmacokinetic Studies Fall Short

Complex drug formulations are where these studies struggle the most. Modified-release tablets, liposomal injections, inhalers, and transdermal patches all have delivery mechanisms that can’t be fully captured by blood samples.

For topical products, a PK study might show no difference in blood levels between two creams. But if one releases the drug faster through the skin, it could cause irritation or reduced effectiveness. That’s why dermatopharmacokinetic methods (DMD) and in vitro permeation testing (IVPT) are gaining traction. One 2014 study showed IVPT using human skin samples was more accurate than clinical trials for topical steroids. Why? Because it mimics what happens at the site of action, not just what shows up in plasma.

Even for oral drugs, excipients-those inactive ingredients like fillers and coatings-can change how a drug dissolves. Two generics with the same active ingredient can have different release profiles because of a change in the binder or coating. That’s why dissolution testing is required alongside PK studies. The FDA demands that dissolution profiles differ by no more than 10%.

And then there’s gentamicin. A 2010 study found that some generic versions failed in vivo despite matching the innovator’s chemical structure, purity, and in vitro dissolution. The problem? Something in the formulation altered how the body processed it. No one could predict it. No in vitro test caught it. Only real-world testing revealed the difference.

The Cost and Complexity Behind the Tests

Running a single bioequivalence study isn’t cheap. It costs between $300,000 and $1 million. It takes 12 to 18 months from formulation to final report. That’s why many generic manufacturers start with the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). If a drug is Class I-highly soluble and highly permeable-it might qualify for a waiver. That means skipping the human study entirely. But only about 15% of drugs meet this criteria.

The FDA now has 1,857 product-specific guidances for bioequivalence. That’s not one-size-fits-all. It’s a maze of rules tailored to each drug. A generic version of metformin has different requirements than a generic version of omeprazole. And for narrow therapeutic index drugs, the rules get even stricter. As of 2023, the FDA has issued special guidance for 28 such drugs.

Global regulators don’t agree on everything. The European Medicines Agency takes a more rigid approach than the FDA. Some countries accept PK studies as proof. Others demand clinical trials. This creates headaches for manufacturers trying to sell the same product worldwide.

What’s Next? The Rise of New Tools

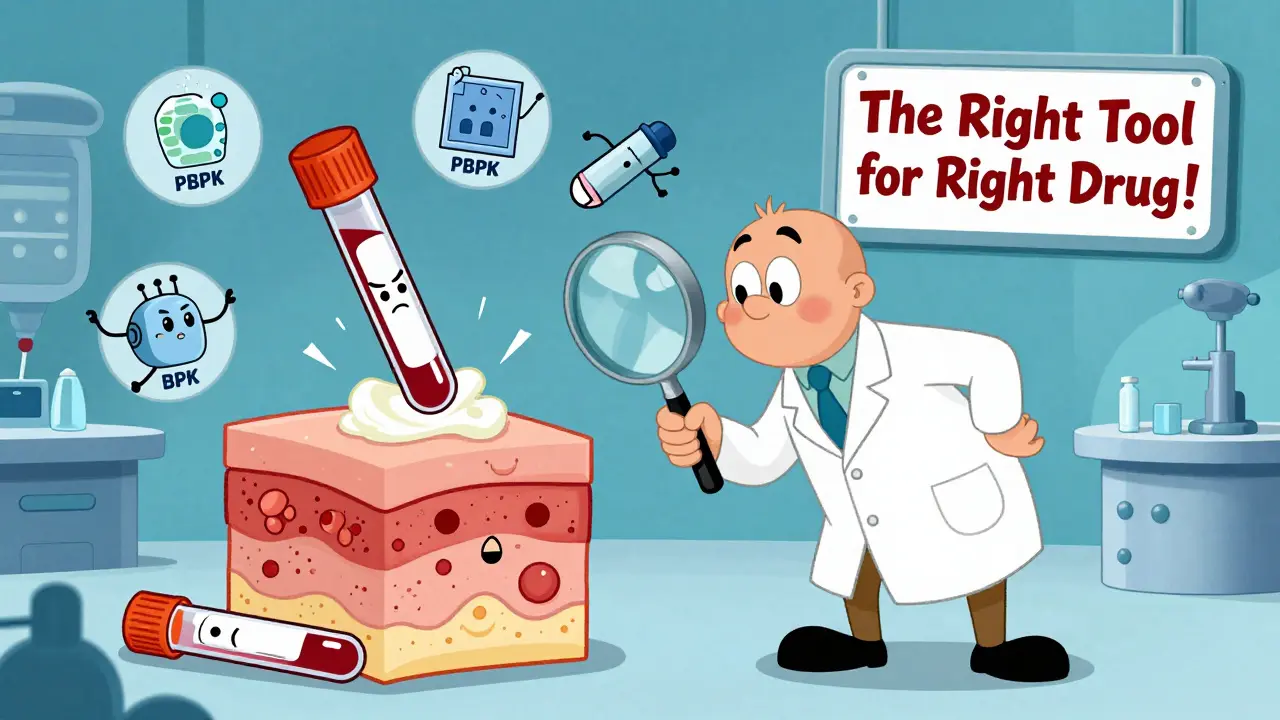

The field is changing. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is now accepted by the FDA for certain drugs. These computer simulations predict how a drug behaves in the body based on its chemical properties, dissolution rate, and human physiology. For simple, well-understood drugs, PBPK can replace human trials entirely.

For topical products, dermatopharmacokinetic methods are proving more reliable than blood tests. One 2019 study showed DMD could detect differences between formulations with over 90% accuracy-far better than traditional PK studies.

Even in vitro testing is being reconsidered. A 2009 PMC paper argued that for some immediate-release drugs, well-designed lab tests could be more consistent and predictive than human trials. Why? Because human variability-diet, metabolism, genetics-adds noise. Lab tests are controlled. They’re repeatable.

Regulators are slowly shifting from a one-size-fits-all model to a product-by-product approach. The goal isn’t to eliminate pharmacokinetic studies. It’s to use them where they work best-and replace them where they don’t.

What This Means for Patients

For most people, generic drugs are safe, effective, and life-changing. Over 95% of generic approvals in the U.S. in 2022 were based on pharmacokinetic studies. And the vast majority of those drugs perform just like the brand.

But if you’re on a drug with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin-don’t assume all generics are interchangeable. Talk to your doctor. Monitor your levels. If you notice changes in how you feel after switching, speak up. Your body might be telling you something the PK study missed.

For complex drugs-inhaled corticosteroids, topical retinoids, or extended-release opioids-the PK study is just the beginning. It’s not the finish line. It’s a checkpoint. And regulators know it.

Final Reality Check

Pharmacokinetic studies aren’t the gold standard. They’re the most practical tool we have right now. They’re reliable for simple, systemic drugs. They’re inadequate for complex ones. And they’re never a substitute for real-world outcomes.

The system works because it’s good enough for most cases. But it’s not perfect. And pretending it is risks patient safety. The future of generic drug approval isn’t about sticking to one method. It’s about using the right tool for the right drug. And that’s a smarter, safer way forward.

Are generic drugs always as effective as brand-name drugs?

For most drugs, yes. Over 95% of generics approved by the FDA meet bioequivalence standards and perform just like the brand. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin or levothyroxine-even small differences can matter. If you switch generics and notice new side effects or reduced effectiveness, talk to your doctor. Your body’s response is the real test.

Why do some generics fail even if they have the same active ingredient?

The active ingredient is only part of the story. Fillers, coatings, and binders can change how quickly the drug dissolves or is absorbed. Two generics with identical active ingredients can behave differently in the body because of these inactive components. That’s why dissolution testing and pharmacokinetic studies are required-to catch these hidden differences.

Can a generic drug pass bioequivalence testing but still be unsafe?

Yes. There are documented cases where generics passed all regulatory tests but caused unexpected reactions in patients. One study found two generics of gentamicin with identical in vitro profiles had different effects on bacterial growth in vivo. Bioequivalence measures absorption-not therapeutic outcome. For some drugs, especially those acting locally or with complex release profiles, PK studies alone aren’t enough to guarantee safety.

What’s the difference between bioequivalence and therapeutic equivalence?

Bioequivalence means two drugs have the same rate and extent of absorption into the bloodstream. Therapeutic equivalence means they produce the same clinical effect-same benefits, same risks. Bioequivalence is a measurable lab result. Therapeutic equivalence is what happens in real patients. One doesn’t always guarantee the other, especially for complex or topical drugs.

Are there alternatives to pharmacokinetic studies for proving generic equivalence?

Yes. For topical drugs, in vitro permeation testing and dermatopharmacokinetic methods are becoming standard. For some oral drugs, physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is accepted by the FDA as a replacement for human trials. And for certain drugs, clinical endpoint studies-measuring actual patient outcomes-are still used, though they’re expensive and rare. The trend is moving toward using the best tool for each drug, not relying on one method for everything.

Evan Smith

January 7, 2026So let me get this straight-we’re letting companies sell pills that pass a blood test but might make you bleed out or clot up? And we call this science? 😅

Annette Robinson

January 8, 2026I’ve been on warfarin for 8 years. Switched generics once and my INR went haywire. Took three weeks to stabilize. My doctor didn’t even blink. If your life depends on this stuff, don’t trust the paperwork-trust your body.

Lois Li

January 10, 2026It’s wild how we treat medicine like a commodity. We want cheap, we get cheap. But when your kid’s asthma inhaler doesn’t work because the propellant changed, no one’s apologizing. The system isn’t broken-it was designed this way.

christy lianto

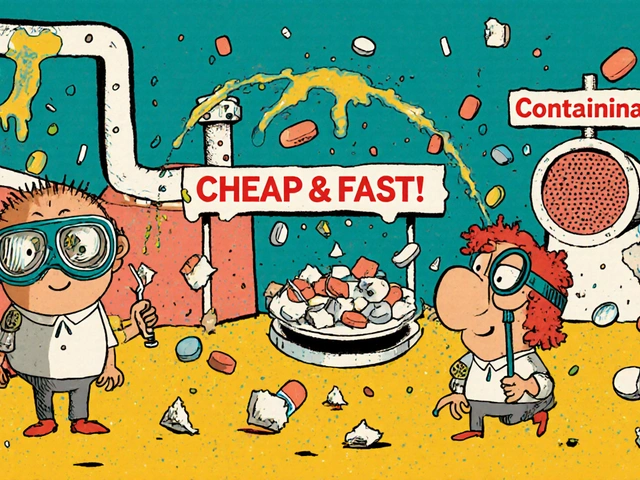

January 11, 2026Let’s be real-pharmacokinetics is just the easiest way to avoid doing actual clinical trials. It’s cheaper, faster, and lets regulators sleep at night. But if you’re on a drug where 5% difference kills you, you’re basically playing Russian roulette with a pill.

Aubrey Mallory

January 13, 2026My mom takes levothyroxine. She’s been on the same generic for years. Then she switched to another one-same active ingredient, same manufacturer, different pill color. She got dizzy, lost her voice, couldn’t sleep. Took her three months to get back to baseline. The FDA says it’s fine. I say: trust the patient, not the spreadsheet.

Donny Airlangga

January 13, 2026It’s not that PK studies are useless-they’re just incomplete. Like judging a car by how fast it goes in a wind tunnel but never taking it on the road. We need more real-world data, not just lab numbers.

Molly Silvernale

January 13, 2026Here’s the uncomfortable truth: we’ve outsourced safety to statistics. We’ve turned human biology into a range-80% to 125%-as if life were a spreadsheet. But bodies aren’t numbers. They’re stories. And sometimes, the story ends before the report does.

Kristina Felixita

January 15, 2026As someone who’s had to switch generics three times because insurance changed, I’ve learned to read the pill shape and color like a barcode. If it looks different? I call my pharmacist. If it feels different? I call my doctor. No one else is watching out for me.

Joanna Brancewicz

January 16, 2026PK studies measure absorption. Not efficacy. Not safety. Not patient-reported outcomes. The disconnect is systemic.

Ken Porter

January 17, 2026Why are we even talking about this? The US makes the best drugs in the world. If you can’t afford the brand, tough luck. Stop complaining about generics-they’re good enough for everyone else.

Luke Crump

January 18, 2026What if the real gold standard isn’t a blood test… but the silence of a patient who doesn’t know they’re being experimented on?

Manish Kumar

January 20, 2026Let me tell you something from India-we don’t have the luxury of fancy PK studies. We use what works. If a generic saves a life and costs 10% of the brand, we take it. Yes, sometimes things go wrong. But when you’re choosing between medicine and hunger, you don’t wait for perfect science. You take what you can get.

Dave Old-Wolf

January 22, 2026I’m a nurse. I’ve seen patients switch generics and suddenly get worse. No one connects the dots. We just assume it’s their condition progressing. But it’s not. It’s the pill. We need better tracking. Like, actual registries.

Prakash Sharma

January 23, 2026India makes 50% of the world’s generics. If we’re so bad, why do you import so much? Your regulators are the ones who approve these. Don’t blame us for your flawed system.

swati Thounaojam

January 24, 2026My aunt switched to a generic and got seizures. Turned out the filler reacted with her meds. No one told her. Now she’s on brand-only. I hope someone fixes this.