When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you might see two options: the brand-name drug and its generic version. They look different. They cost very different prices. But are they the same? The answer lies in two closely linked but fundamentally different concepts: bioavailability and bioequivalence. Understanding how they work helps explain why generics are safe, why some people notice differences, and how regulators make sure you get what you’re paying for.

What Bioavailability Really Means

Bioavailability answers one simple question: How much of the drug actually gets into your bloodstream? It’s not about how much you swallow-it’s about how much your body can use.

Take a pill. It goes through your stomach, gets absorbed in your intestines, then travels to your liver before entering your blood. Along the way, some of it breaks down. Some gets stuck. Some never makes it past the gut. For example, if you take 100 mg of a drug, only 60 mg might actually reach your blood. That means its bioavailability is 60%. That’s not failure-it’s normal. Most oral drugs have bioavailability between 30% and 80%.

There are two types of bioavailability you need to know:

- Absolute bioavailability compares how much of the drug enters your blood after taking it by mouth versus getting it through an IV. IV is 100% because it goes straight in. Everything else is measured against that.

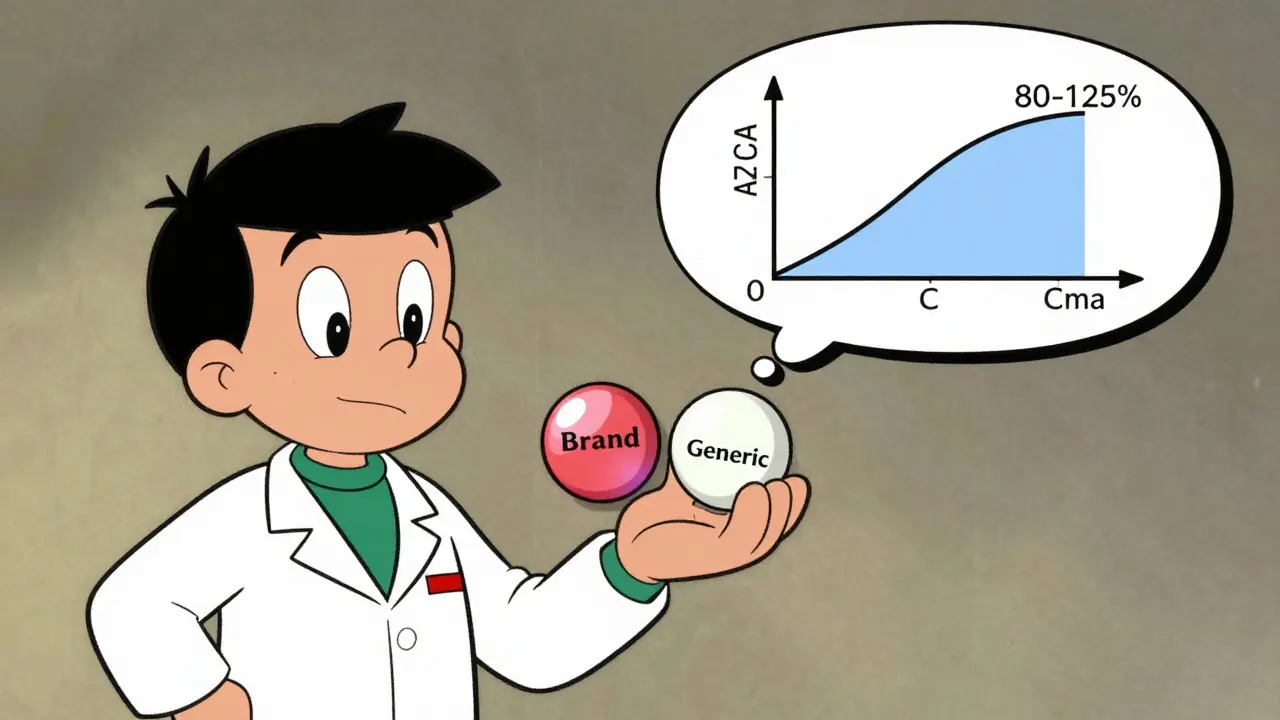

- Relative bioavailability compares two different versions of the same drug-say, a brand-name tablet versus a generic one. Both are taken by mouth. Which one gets more into your blood? That’s what this measures.

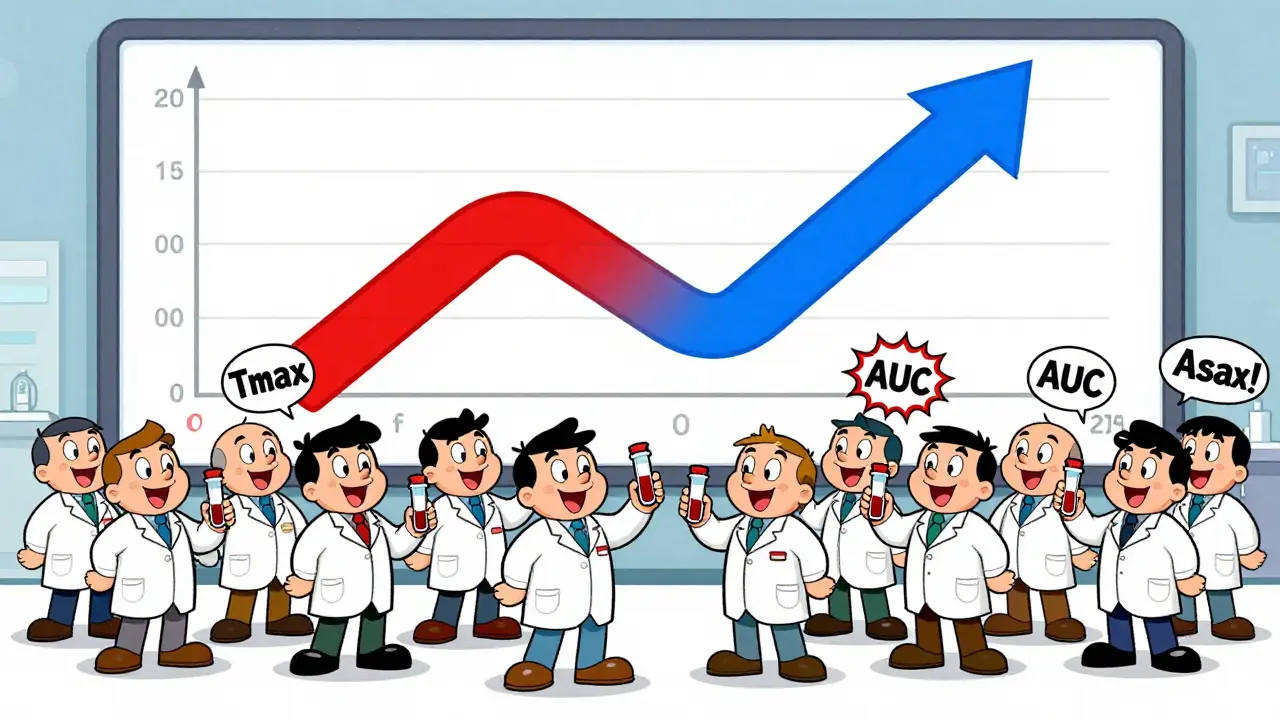

Two numbers tell the whole story: AUC and Cmax.

- AUC (Area Under the Curve) measures total drug exposure over time. Think of it as the total amount of medicine your body sees from start to finish.

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration) is the highest level the drug reaches in your blood. This tells you how fast it gets absorbed.

These aren’t just lab terms. They’re what doctors and regulators use to decide if a drug works as expected. If a drug has low bioavailability, it might need a higher dose. If it’s too high, it could cause side effects. Bioavailability is about understanding a single product’s behavior.

What Bioequivalence Actually Checks

Bioequivalence doesn’t care about one drug. It cares about two. Specifically, it asks: Is the generic version just as good as the brand?

This is where things get technical-and fair. The FDA and other global regulators don’t just say, “They look alike, so they’re the same.” They run real studies. In a typical bioequivalence study, 24 to 36 healthy volunteers take both the brand and the generic, in random order, under fasting conditions. Blood samples are taken every hour or so over 72 hours. Then they plot the concentration curves.

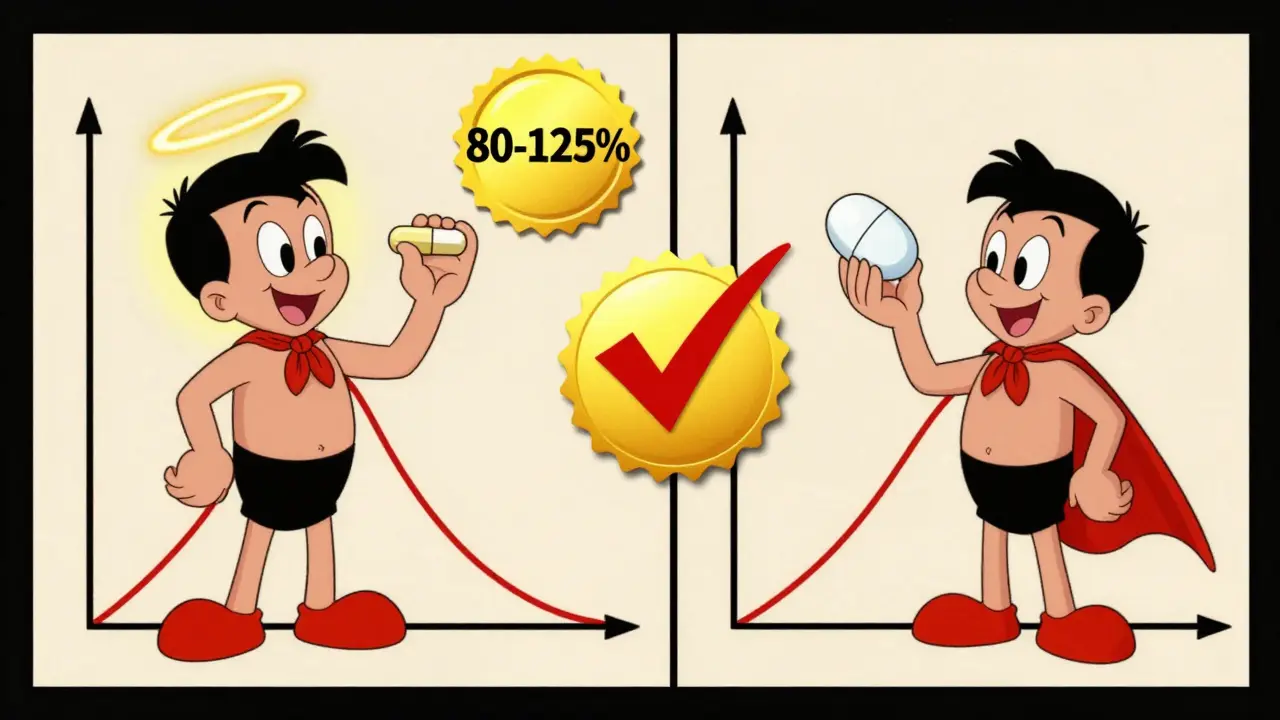

The magic number? 80% to 125%.

Here’s how it works: Researchers calculate the ratio of the generic’s AUC and Cmax to the brand’s. Then they apply a statistical test to find the 90% confidence interval. If that interval falls entirely between 80% and 125%, the two products are considered bioequivalent. That means the generic delivers between 80% and 125% of the brand’s drug exposure. Not 100%-but close enough to be safe.

Why not 100%? Because biology isn’t perfect. People absorb drugs differently. Even the same person on different days might absorb slightly more or less. The 80-125% range accounts for natural variation. It’s not a loophole-it’s science.

There’s one more number: Tmax (time to reach peak concentration). If the generic peaks in 1.5 hours and the brand in 1 hour, that’s not automatically a problem. Minor differences in Tmax can come from differences in tablet coating or filler ingredients-not the active drug itself. As long as AUC and Cmax are within range, it’s still bioequivalent.

What’s the point? If two drugs are bioequivalent, they’re considered therapeutically equivalent. That means: same effect. Same side effects. Same risk. No guesswork.

The Key Difference: One vs. Two

Bioavailability is about a single product. Bioequivalence is about a comparison.

You can measure bioavailability for a new drug during development. You can test how food affects it. You can tweak the formula and see how absorption changes. But bioequivalence? It only happens when you have two products side by side.

Think of it like two cars. Bioavailability tells you how far one car can go on a full tank. Bioequivalence tells you if two different models of the same car get the same mileage under the same conditions.

Both rely on the same measurements-AUC and Cmax. But bioavailability is descriptive. Bioequivalence is comparative. And that’s why generics can be approved without doing full clinical trials on every condition the drug treats. If they match the brand’s bioavailability profile, regulators assume the therapeutic effect will be the same.

When the Rules Get Tighter

Not all drugs are treated the same. For most, 80-125% is fine. But for some, even a 10% difference can be dangerous.

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) are the problem children. These are medicines where the difference between a helpful dose and a harmful one is tiny. Think warfarin (blood thinner), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), or phenytoin (seizure control).

For these, the standard 80-125% range is too loose. The FDA has special rules. For warfarin, the AUC ratio must fall between 90% and 112%. For levothyroxine, the range is 90-111%. That’s a much tighter net.

Why? Because a 20% drop in thyroid hormone might cause fatigue and weight gain. A 20% spike might trigger heart rhythm problems. With NTI drugs, small changes matter. That’s why pharmacists sometimes recommend sticking with the same brand-even if a generic is approved.

And here’s the real-world evidence: A 2023 survey by the American Pharmacists Association found that after switching 1,247 patients from brand to generic antihypertensives, only 17 reported issues. Of those, only 4 had confirmed biological differences. The rest? Probably coincidence, stress, or other factors.

Why Some People Still Notice Differences

If bioequivalence is so solid, why do some patients swear their generic doesn’t work the same?

It’s not always about the drug. Sometimes, it’s about the fillers. Generics use different inactive ingredients-dyes, binders, coatings. These don’t affect absorption, but they can change how the pill tastes, how fast it dissolves, or how it feels in your stomach. For someone with a sensitive gut, that might cause nausea or bloating. That’s not bioequivalence failure-that’s intolerance.

Also, brand-name drugs often have better quality control. Their manufacturing is consistent. Some generics, especially from overseas, have had issues with contamination or inconsistent dosing. But these are rare-and regulators catch them. The FDA inspects factories. If a batch fails, it’s pulled.

And then there’s the placebo effect. If you believe the brand is better, your body might respond better-even if the drug is identical. Studies show this happens more than you think.

Bottom line: Bioequivalence doesn’t guarantee identical experience. It guarantees identical drug exposure. Everything else is noise.

How Testing Works in Practice

Bioequivalence studies aren’t done in a lab with a single sample. They’re full clinical trials.

Each study:

- Uses healthy volunteers (to avoid confounding diseases)

- Follows a crossover design (each person takes both drugs, in random order, with a washout period)

- Is done under fasting conditions (to remove food interference)

- Collects 12-18 blood samples over 72 hours

- Uses sensitive lab equipment to measure drug concentration

It’s expensive. It takes months. A single study can cost over $500,000. That’s why generics are cheaper-not because they’re low quality, but because they don’t have to repeat the 10-year development cycle of the original drug.

For complex drugs-like inhalers, creams, or injectables-bioequivalence gets trickier. You can’t just measure blood levels. For topical steroids, you need to measure skin absorption. For inhalers, you need to check lung deposition. Regulators are still figuring out the best ways to test these. Some are exploring in vitro tests (lab-based dissolution) as a shortcut, but for now, most still require human studies.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. They save patients and insurers over $200 billion a year. Without bioequivalence standards, that wouldn’t be possible.

Every generic approved since 2010 has been tested against this standard. And the data is clear: 99.7% met the criteria. There’s no evidence that generics are less safe or less effective when they pass bioequivalence testing.

Regulators aren’t perfect. But the system works. It’s based on decades of pharmacokinetic research, real-world data, and clinical experience. The 80-125% rule? It was debated, tested, and refined. It’s not arbitrary. It’s math.

For most people, switching from brand to generic is safe, effective, and saves money. For those with NTI drugs, doctors and pharmacists already know to be cautious. The system has checks built in.

So next time you’re handed a generic, remember: it didn’t just get approved because it looks like the brand. It passed a rigorous test. And that test? It’s built on bioavailability. And it’s measured by bioequivalence.

Can a generic drug have different side effects than the brand?

The active ingredient is identical, so the side effects should be the same. But inactive ingredients-like dyes, fillers, or coatings-can sometimes cause reactions in sensitive people. For example, a gluten-containing filler might trigger symptoms in someone with celiac disease. That’s not a bioequivalence issue-it’s an allergy or intolerance. Always check the inactive ingredients list if you have sensitivities.

Why do some generics cost so much less than others?

It’s about competition. When multiple companies make the same generic, prices drop. The first generic to enter the market often has a slight price advantage. As more companies join, prices fall further. A drug with 10 generic makers can cost 90% less than the brand. A drug with only one generic may still cost 50-70% less. It’s supply and demand, not quality.

Is bioequivalence testing required in Australia?

Yes. Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) follows the same international standards as the FDA and EMA. All generics approved in Australia must demonstrate bioequivalence using the 80-125% confidence interval rule. The TGA also audits manufacturing sites and requires ongoing quality control.

Do I need to tell my doctor if I switch from brand to generic?

It’s a good idea, especially if you’re on a narrow therapeutic index drug like warfarin, levothyroxine, or epilepsy meds. Your doctor can monitor your blood levels or symptoms. For most drugs, though, switching is routine. Pharmacists are trained to confirm bioequivalence before dispensing.

What happens if a generic fails bioequivalence testing?

It’s not approved. If a company submits a generic for approval and the data shows the AUC or Cmax ratios fall outside 80-125%, the FDA (or equivalent agency) rejects it. The company can fix the formulation and resubmit. Many generics fail the first time. That’s why there are fewer generics than you might expect for some drugs-because the bar is high.

Maddi Barnes

February 21, 2026Okay, so let me get this straight-bioequivalence is basically the pharmaceutical version of ‘looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, let’s not overthink it’? 😅 I love that the FDA doesn’t demand 100% identical absorption. Biology is messy, people! My dog has better consistency than my morning coffee. Also, the 80-125% range? That’s not a loophole-it’s a *human* loophole. We’re not robots. We’re squishy, inconsistent, snack-driven organisms. And yet, somehow, this works. 🤯

Courtney Hain

February 22, 2026You think this is science? HA. The real story is Big Pharma paying off regulators to let generics in so they can charge 10x more for the brand. Why do you think the brand versions always have that ‘premium’ packaging? They’re selling placebo. The FDA’s 80-125% rule? Total scam. I’ve seen people go from brand to generic and start having seizures. They’re not ‘tolerance’-they’re COVER-UPS. And don’t get me started on overseas labs. I’ve got cousins who work in India. You wouldn’t believe what’s in those pills. 🤫

Greg Scott

February 24, 2026Honestly? I’ve been on generic levothyroxine for years. No issues. My TSH is stable. My energy’s fine. I used to be paranoid too-until I got the lab results. The science isn’t perfect, but it’s good enough. And yeah, sometimes the fillers mess with your stomach. But that’s not the drug’s fault. It’s like switching from Coke to Pepsi-different soda, same caffeine. Chill out.

Davis teo

February 25, 2026I just switched to a generic for my blood pressure med and I swear I felt like a zombie for two weeks. My wife said I was ‘duller.’ I told her I was just ‘bioequivalent.’ She didn’t laugh. I’m not crazy. I’ve got the receipts. My pharmacist said ‘it’s fine’ but I’m filing a complaint. Someone needs to test this stuff on real people-not college kids on an empty stomach. I’m not a lab rat.

James Roberts

February 26, 2026Let’s be real: the 80-125% range? Brilliant. It’s not arbitrary-it’s statistically sound. And yes, NTI drugs get tighter limits. That’s not a flaw-it’s a feature. The system is designed to catch outliers. Also, the fact that 99.7% of generics pass? That’s not luck. That’s rigorous science. And for the conspiracy folks? If generics were dangerous, we’d be seeing mass hospitalizations. We’re not. We’re seeing people save $300/month. That’s not a conspiracy. That’s capitalism working. 🤝

Danielle Gerrish

February 26, 2026I can’t believe people still doubt this. I’m a nurse. I’ve seen patients cry because they can’t afford the brand. I’ve seen them get sicker because they skip doses. Then they switch to generic-and boom. Same results. Same labs. Same life. The only difference? They’re not bankrupt. The real tragedy isn’t the pill-it’s the people who think they’re being ‘cheated’ by cheaper medicine. You’re not being ‘scammed.’ You’re being helped. 🙏

madison winter

February 28, 2026Interesting. Makes me wonder if bioequivalence is just another way of saying ‘close enough for government work.’

Jeremy Williams

March 2, 2026The regulatory framework for bioequivalence is one of the most elegant applications of pharmacokinetic modeling in modern medicine. The use of AUC and Cmax as primary endpoints, coupled with a 90% confidence interval anchored within the 80–125% range, reflects a profound understanding of inter-individual variability. This is not a compromise-it is a principled, evidence-based standard grounded in decades of clinical research. The fact that it is adopted globally-from the FDA to the TGA to the EMA-speaks to its scientific robustness. We are not merely approving pills; we are validating physiological equivalence under controlled, reproducible conditions.

Benjamin Fox

March 2, 2026USA BEST. We don’t need some foreign lab making our medicine. If it’s not made in America, it’s a gamble. Generic? Maybe. But only if it’s made in Ohio. 🇺🇸

Jonathan Rutter

March 3, 2026You people are so naive. You think the FDA cares about you? They care about the bottom line. They let generics through because they’re cheaper to approve. The real danger? The fact that you’re trusting a system that’s been corrupted by corporate lobbyists. I’ve seen the emails. I’ve read the reports. They don’t test the pills-they test the paperwork. And if you think your life is worth $0.50 a pill, you’ve already lost.

Jana Eiffel

March 4, 2026Bioavailability and bioequivalence are not merely pharmacological constructs-they are epistemological inquiries into the nature of therapeutic identity. When we assert that two formulations are equivalent, we are not merely comparing concentration curves; we are negotiating the ontological continuity of the therapeutic self. The 80–125% interval, then, is not a statistical convenience, but a hermeneutic threshold-a liminal space where the material and the metaphysical converge. One might say: in the quiet hum of a tablet dissolving, we find not just pharmacokinetics, but the fragile poetry of human trust.

aine power

March 5, 2026Lol. You wrote a textbook. The answer is: yes, they’re the same. Move on.

Tommy Chapman

March 6, 2026If you’re taking generics, you’re basically gambling with your life. I don’t care what the FDA says. I only take brand. My body knows. And if you’re saving money by risking your health? You’re not smart. You’re stupid. And if you’re from another country? You’re lucky we let you use our medicine at all.